ADS and how to change Scots taxes

Reporting from Holyrood on a Finance and Constitution Committee meeting, Donald Drysdale finds that lessons are being learnt from shortcomings in the Additional Dwelling Supplement.

LBTT and ADS

The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Scotland) Act 2013 introduced LBTT to replace stamp duty land tax (SDLT) in Scotland with effect from 1 April 2015.

The LBTT (Amendment) (Scotland) Act 2016 introduced the Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS) as a 3% surcharge on acquisitions of additional properties for £40,000 or more from 1 April 2016. ADS was increased to 4% from 25 January 2019.

ADS was justified on several grounds: to buttress the Scottish budget against block grant adjustments arising from the SDLT higher rate for additional dwellings; to protect first-time buyers in Scotland; and to prevent market distortions from any influx of purchasers from south of the border.

In general, ADS paid when acquiring a replacement main residence can be reclaimed where the former main residence is disposed of within the next 18 months.

Flaws in ADS

One of the key policy objectives of the 2016 Act was that married couples, civil partners and cohabitants should be treated for ADS as one economic unit, to prevent properties being moved between individuals for tax avoidance purposes.

Paradoxically, ADS charged where couples jointly acquired a home to replace one that was owned by only one of them could not be reclaimed, as only one name had appeared on the title deeds.

Thus a couple was treated as one economic unit when determining if ADS applied, but not when determining whether ADS should be repaid.

In June 2017 this anomaly was addressed by secondary legislation, which could not be back-dated. Later, primary legislation (LBTT (Relief from Additional Amount) (Scotland) Act 2018) corrected the position from 1 April 2016.

Other flaws in ADS remain, and on 29 May 2019 the Scottish Parliament’s Finance and Constitution Committee took evidence from interested parties in a roundtable format.

Committee proceedings

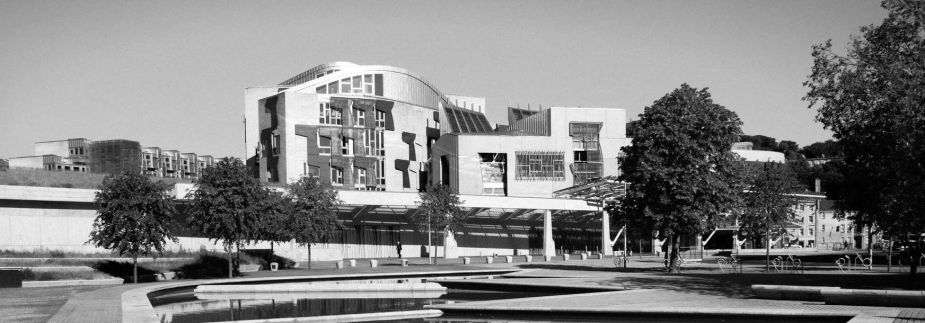

The Committee’s 1-hour evidence session about ADS was convened by Bruce Crawford MSP. The official report on the meeting and a video recording are available online.

Among attendees were Charlotte Barbour, Director of Tax at ICAS; Elaine Lorimer, Chief Executive of Revenue Scotland; and representatives from CIOT, the Law Society of Scotland and various organisations representing property interests.

Discussing how ADS has been operating in practice, Revenue Scotland emphasised the difference between LBTT as a tax on land transactions and ADS as a tax that varies according to the personal circumstances of the taxpayer.

ADS has required complex published guidance, with over 75 worked examples, and ADS accounts for 24% of incoming calls to Revenue Scotland’s support desk. If ADS could be simplified and anomalies removed, many such calls would no longer be required.

Charlotte Barbour from ICAS pointed out that a tax on transactions and one based on personal circumstances will never fit easily together. ICAS wants to see better policy processes, and better consultation on draft legislation to ensure that it works as intended.

The Law Society saw ADS as a complex tax which had been brought in over too short a timescale. It considered the new relief for couples helpful but noted that it failed to address all anomalies. For example, divorcing couples with property still in joint names could face ADS unfairly.

Revenue Scotland wanted ADS legislation which could operate efficiently but acknowledged that it was incredibly difficult to define clearly what was to be taxed.

The Scottish Property Federation (SPF) queried the efficiency of ADS, given that up to 30% of revenues collected are subsequently repaid. I believe this aspect of ADS can put unreasonable pressure on taxpayers moving house, at a time when their resources are inevitably stretched.

Interestingly, SPF predicted increasing problems with ADS over time, as interests in dwellings inherited – e.g. from deceased parents – could be taken into account as additional dwellings owned by younger generations.

Murdo Fraser MSP was concerned for taxpayers who expect repayment of ADS but then find they are not entitled to it. The fact that many are in this position seems to be confirmed by statistics from Revenue Scotland and anecdotal evidence from the Law Society.

ICAS, CIOT and the Law Society said that, while SDLT had been dealt with primarily by conveyancing solicitors, LBTT and ADS are proving much more complex – requiring advice from tax specialists.

CIOT spoke about ADS triggering a big increase in taxpayers’ queries to accountants about acquiring residential properties, particularly joint acquisitions with children or parents, and situations involving divorce or co-habitation.

Housing supply

The impact of LBTT and ADS on small developers was discussed, amid concerns that development in Scotland is being stifled. They feel disadvantaged – paying residential rates of LBTT, plus ADS as a slab tax, and rarely qualifying for multiple dwellings relief.

Revenue Scotland expressed doubts that ADS was stifling development, since the annual number of notifiable transactions for LBTT had remained more or less unaffected by the introduction of ADS.

Local authorities frequently acquire individual dwellings on the open market to support strategic and operational housing objectives. They accept that LBTT and ADS apply to them, but question whether this was intended, particularly as housing associations are exempt.

The impact of ADS on the private rented sector is hard to quantify. It tends to reduce the number of properties available, but many landlords are leaving the sector for other reasons. Charlotte Barbour spoke of buy-to-let landlords being adversely affected by UK-wide restrictions on interest relief and prospective changes to capital gains tax rules.

Generally, it was noted that anomalies similar to those affecting LBTT and ADS had arisen too in relation to SDLT. In some cases, guidance had been improved. In others, the law had been amended, and this proved easier at Westminster where the Finance Bill process is well-established.

Lessons to be learnt

Holyrood needs to learn that resolving tax anomalies can create new loopholes – a lesson already known only too well at Westminster. For this reason, ICAS and other bodies believe that periodic Scottish Finance Bills would help in methodically maintaining all devolved tax legislation.

Such a Finance Bill, perhaps annually or once every two years, would provide a vehicle for care and maintenance of taxes and policy changes. Charlotte Barbour explained that ongoing discussions with the Scottish Government are exploring this as a means of developing better processes which would allow proper scrutiny.

And finally, practitioners should not miss a practice development opportunity to advise on LBTT and ADS. Noting the extra pressures on conveyancers, Isobel d’Inverno of the Law Society caused some amusement by saying: “It is a sorry state of affairs if people cannot buy a house without asking an accountant how much it will cost.”

Article supplied by Taxing Words Ltd

By Donald Drysdale for ICAS

By Donald Drysdale for ICAS